Texas doesn’t have a mile-high city, however Fort Davis comes close at 4,892 feet. The small unincorporated town is nestled in the foothills of the Davis Mountains, where bears and mountain lions and elk stalk amongst pine-forested sky islands. Fort Davis is the seat of Jeff Davis County, whose population of 1,900 is spread out amongst 2,265 square miles, half larger than Rhode Island. The sparsely inhabited desert nation of Mongolia has almost 7 times the population density of Jeff Davis County. Odessa, the nearby city to Fort Davis, is 2 and a half hours away. The state Capitol is 6 and a half.

For Graydon Hicks III, the far-flunged-ness of Fort Davis belongs to its appeal. He likes the high and lonely feel of his home town—the “prettiest in Texas,” he says. But nowadays, it has actually never ever felt even more from the state’s political center of mass.

For years, Hicks, the superintendent of Fort Davis ISD, has actually been seeing, helplessly, as a slow-motion catastrophe has actually unfolded, the outcome of a problematic and resource-starved public-school financing system. Over the last years, moneying for his little district, which serves simply 184 K–12 trainees, has actually drooped even as expenses, driven by inflation and ever-increasing state requireds, have actually skyrocketed. The mathematics is plain. His austere budget plan has actually hovered around $3.1 million a year for the previous 6 years. But the state’s infamously intricate school financing system just enables him to generate about $2.5 million a year through real estate tax.

Hicks has actually hacked away at all however the most important aspects of his budget plan. More than three-quarters of Fort Davis’s expenses can be found in the form of payroll, and the beginning income for instructors is the state minimum, simply $33,660 a year. There are no finalizing bonus offers or stipends for extra instructor accreditations. Fort Davis has no art instructor. No snack bar. No curator. No bus paths. The track group doesn’t have a track to train on.

But Hicks can’t cut his escape of this monetary crisis. This academic year, Fort Davis ISD has a $622,000 financing space. To comprise the distinction, Hicks is using cost savings. Doug Karr, a Lubbock school-finance expert who examined the district’s financial resources, said Fort Davis ISD was “wore down to the nub and the nub’s all gone. And that pretty much describes small school districts.”

“I am squeezing every nickel and dime out of every budget item,” Hicks said. “I don’t have excess of anything.” When I joked that it seemed like he was holding things together with duct tape and baling wire, he didn’t laugh. He said: “I literally have baling wire holding some fences up, holding some doors up.”

The district’s crisis comes at a time when the state is flush with an unmatched $33 billion budget plan surplus. Hicks is a self-described conservative, however he believes the far ideal is attempting to destroy public education. For years, the state has actually starved public schools of financing: Texas ranks forty-second in per-pupil spending. And yet Governor Greg Abbott is spending huge political capital on promoting a school coupon strategy, which would divert taxpayer funds to independent schools. Public education, Abbott has actually consistently said, will stay “fully funded,” though public-education spending is lower now than when he took workplace in 2015, and the Legislature just recently passed a $321.3 billion budget plan without any pay raise for instructors and really little brand-new financing for schools. Unable to get his coupon strategy through the routine legal session, Abbott is threatening to call legislators back to Austin till he gets his method.

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, long a champ of coupons, is backing legislation that would try to calm rural Republican lawmakers—a bloc long cautious of coupons—by providing $10,000 to districts that lose trainees to independent schools. Hicks can hardly include his anger when he hears such talk. He has actually been lobbying state leaders for many years to repair the debilitating monetary scarcities that pester districts like his. “Take your assurances and shove ’em up your ass,” he says, prior to softening a bit. “I’m so tired. I’m so frustrated. We have tried. I have fought and fought and fought.”

With each passing month, his rural district inches more detailed to monetary destroy. If absolutely nothing modifications by next summer season or fall, Fort Davis will have diminished its cost savings. He doesn’t understand the specific day that his school district will go broke, however he can see it coming.

It’s simple sufficient to comprehend the basic issue in Fort Davis. But what’s going on below the surface area is another story.

During my twenty years of reporting on Texas politics, I’ve frequently heard that just a handful of individuals in the state comprehend the school-finance system, with its complex solutions, allocations, optimum compressed tax rates, ensured yields, and “golden pennies.” A previous coworker of mine, who when invested months attempting to understand the subject, cautioned me versus discussing it. Karr, the school financing expert, compares the procedure of understanding our public education financing to experiencing a fire at a roadside cotton gin on some lonesome West Texas highway. “You drive off into that smoke and you might never drive out,” he said. “You might end up getting killed.”

A comprehensive description of the system is the things of graduate theses, however the broad strokes are uncomplicated enough. How a school district is moneyed starts with 2 essential concerns: How much money is the district eligible for? And who spends for it?

Here it’s valuable to utilize an age-old school financing example: containers of water. The size of a school district’s container—just how much money it’s entitled to—is mostly identified by the variety of trainees in participation. Every district gets a minimum of $6,160 per student, a quantity referred to as the basic allocation, an approximate number thought up by the Legislature and altered according to legislators’ impulses.

From there, the Texas Education Agency changes for the commonly variable expenses of trainees’ instructional requirements. For example, districts get additional for special-ed trainees, multilingual trainees, and dyslexic trainees. There is likewise extra financing available for fast-growing districts (which battle to stay up to date with the expenses of development) and little districts (which do not have economies of scale). The resulting number, the so-called Tier I privilege, represents what the state thinks to be enough financing for each district to offer a basic education to its trainees.

Next comes the concern of who pays. The $64 billion public-education system, which makes up a greater portion of the state’s budget plan than any other function, has actually long been developed on a collaboration in between regional neighborhoods and the state. Currently regional taxpayers put in about 53 percent, the state contributes 38 percent, and the feds get the rest. But that’s a typical throughout the entire system. At the private district level, the share can differ substantially. Property-poor districts might not have the ability to produce sufficient tax dollars to spend for their privilege—to fill their container. In that case, the state will comprise the distinction. Property-rich districts, on the other hand, might have the ability to cover their privilege without any state contributions and still have lots left over, a few of which can be invested in your area and a few of which is sent to the state for redistribution to poorer districts. Their containers runneth over.

Hicks, the Fort Davis superintendent, is a trainee of this byzantine structure. He needs to be. Many small-district superintendents can’t pay for CFOs and need to depend on themselves to find out how to squeeze every cent out of a stingy system.

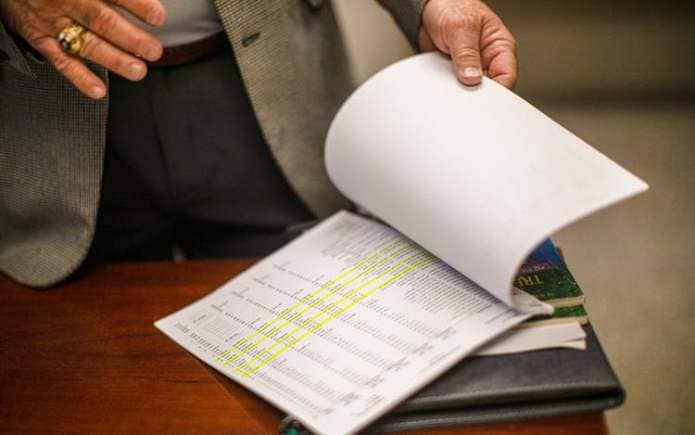

Using a number of spreadsheets, Hicks explained how the system had actually stopped working Fort Davis. One of those spreadsheets was developed by Omar Garcia, a financial investment lender who formerly worked for the Texas Education Agency (TEA), assisting school districts approximate state financial assistance. (In school financing circles, Garcia has actually accomplished first-name-only status, with one authorities calling him a “genius” in a 2022 homage video.) The Omar spreadsheet consists of a minimum of 120 connected worksheets, with names such as “M&ODetail2223-HB3”—an excessive concatenation of information, solutions, and variables stemmed from the decades-long accretion of law that builds up in layers, like an ancient archeological website. Following the money through the interlocking spreadsheets can be infuriating. “What reasonable person would say this makes sense?” says Hicks. “It’s totally bizarre.”

Hicks is not alone in believing the opaqueness is deliberate. “They make it just as complicated as they can,” he said of state authorities. “Because how do you explain something so complicated to the average voter?” In other words, if constituents can’t quickly comprehend the bewildering and needlessly knotty structure, it’s harder to hold authorities responsible for budget plan choices.

Though the spreadsheets might be head-spinning, they narrate. In a state where some rich rural neighborhoods build $80 million high school football arenas, Fort Davis ISD is among lots of rural neighborhoods actually having a hard time to keep the lights on.

I initially spoke with Hicks in March 2021, when he emailed state authorities and reporters with an alarming message: “What, exactly, does the state expect us to do? What more can we do? What more do our children need to be deprived of? At what point does our community break?” Hicks has actually received couple of responses, even as his scenario has actually grown more desperate.

When I visited him in April, we fulfilled in his workplace, where he keeps a book on Texas weapon laws, a picture of his West Point 1986 finishing class (that included Donald Trump’s secretary of state Mike Pompeo), and a list of quotes from General George Patton (“Genius comes from the ability to pay attention to the smallest details”). Hicks, who’s stout and major and talks in a sort of shout-twang due to the fact that of partial hearing loss, used a cross embellished in the colors of the American flag. He aspired to reveal me the great line he strolls in between financial vigilance and dilapidation. The very first lesson came as he stood from his desk and I discovered the holstered pistol on his hip. The district, he explained, can’t pay for to employ a school gatekeeper, so he and eleven other district workers bring guns.

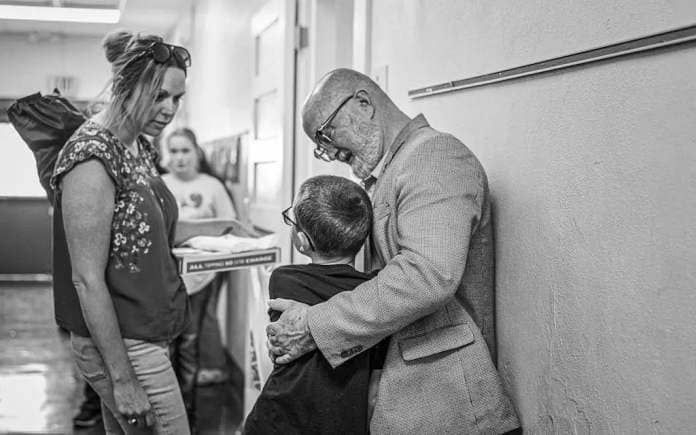

His family has actually remained in the location considering that the 1870s, when federal soldiers still pursued Comanche and Apache from the town’s name fort. His terrific uncle was among the very first superintendents of Fort Davis ISD. (At one point, Hicks revealed me a copy of his great-uncle’s 1942 master’s thesis, “The Early Ranch Schools of the Fort Davis Area.”) Later, as we were walking around school, Hicks’s ten-year-old grand son, a thin fourth-grader using blue-rimmed glasses and blue denims tucked into a set of cowboy boots, added to Hicks and provided him a hug.

Both the grade school and the high school—where Hicks finished in 1982—were integrated in 1929, Hicks explained. Walking through their timeworn corridors is to go back in time. In locations, the plaster is exfoliating the initial adobe walls. The grade school health club flooring is bubbling up due to the fact that of a leakage under the structure. The wood seats in the high school auditorium have actually never ever been changed. The urinals in the grade school are initial too. The latest training center, a science laboratory, was integrated in 1973. In the summer season, Hicks trims the football field, the very same one he used 5 years back. “Every bit helps,” he said.

The financing challenges produce all way of causal sequences. Hicks has difficulty recruiting and maintaining instructors, and some trainees wander away from school without extracurriculars to hold their interest. “You lose teachers, then you start losing kids, and then your funding gets worse,” he said. “It’s a circle-the-drain kinda thing. And it’s really speeding up for Fort Davis.”

The very first issue is the size of the district’s container. For the last years, TEA has actually computed that Fort Davis’s Tier I yearly allocation is in between $2 million and $2.5 million, well except its already simple $3.1 million budget plan.

And then there’s the matter of how that container is filled. In the 2011–2012 academic year, the state covered two-thirds of Fort Davis’ privilege, about $2.1 million. Today, it chips in about $150,000, a 93 percent decline. How to explain that modification?

The causes are lots of, however each of them indicates systemic issues with the present school financing system. Like lots of districts, Fort Davis ISD is handling the fallout from COVID-19. Some trainees never ever went back to school after the pandemic; others have spotty participation. Texas is among the couple of states that offers financing based upon participation instead of registration. When a trainee leaves or misses out on classes, the district loses dollars. Schools throughout the state are getting hammered by a drop in registration, however little districts are especially susceptible—every trainee lost represents a greater percentage of overall income.

The state enables districts to raise more money by imposing an extra tax of as much as 17 cents per $100 of property, so-called enrichment or Tier II financing. Fort Davis creates as much as it can through Tier II, about $270,000 approximately, prior to it faces yet another constraint: due to the fact that the district is thought about property-rich, it needs to send out money back to the state beyond a specific point. Enrichment financing offers Fort Davis the capability to grow its container, however insufficient to satisfy its requirements.

Property worths are yet another issue. Since 2016, property worths in Fort Davis have almost doubled. Given that Texas schools are moneyed in big part by regional real estate tax, that would appear to represent a windfall for Fort Davis ISD. But in truth it has had the opposite impact.

As property worths have actually skyrocketed, state help has actually decreased. That’s by style. “TEA doesn’t judge a school district’s wealth by how much money they’ve got in the bank. They judge it by the property value,” said Bob Popinski, the senior director of policy at Raise Your Hand Texas, a pro–public education not-for-profit established by H-E-B chairman Charles Butt. “And so when a school district’s property value is going up, TEA takes the perspective that those people are getting wealthier because they’ve got more taxable wealth.”

The concept is that skyrocketing property worths will yield more regional tax dollars, and state help isn’t required as much. But the reality is far various in Fort Davis and some other rural districts. Part of the issue is that the regional appraisal district and the state comptroller can’t settle on the worth of property in the county. For example, for the present academic year, the Jeff Davis County Appraisal District pegged the overall worth of property in Fort Davis ISD at $233 million. But the comptroller discovered it was 22 percent greater than that, at $284.4 million.

And here’s the rub: when there is substantial divergence in between the appraisal district and the comptroller, the Texas Education Agency need to by law side with the comptroller. This produces a “double-whammy,” says Popinski. The company identifies what it believes the district requires based upon the greater comptroller worth, therefore lowering the quantity of state help, however the district can just gather taxes on the lower quantity.

Nearby Alpine ISD is dealing with a comparable issue, its superintendent Michelle Rinehart informed me. Over the previous 2 years, due to argument over property worths, Alpine schools lost almost $1 million from the state—a considerable amount for a cash-strapped district with a $12 million budget plan. The bottom line: the state treats districts like Fort Davis and Alpine as if they were abundant when they’re really rather poor. And this state of affairs is especially exceptional considered that simply a couple of years ago state leaders were promoting an apparently generational financial investment in public education.

In June 2019, the Big Three figures in state federal government—Abbott, Patrick, and after that–House Speaker Dennis Bonnen—collected at a grade school in Austin for an almost giddy bill-signing event. As a bipartisan group of legislators seen, Abbott signed into law House Bill 3, an $11.6 billion package of real estate tax cuts and education financing that had actually received near-unanimous assistance in both the House and Senate, a rarity in the extremely polarized Legislature. “This one law does more to advance education in the state of Texas than any law that I have seen in my adult lifetime,” said Abbott.

For almost a year, a selected commission of specialists had actually fulfilled to go over how to upgrade the school-finance system, releasing a report in December 2018 that got in touch with the Lege to “redesign the entirety of our state’s funding system to reflect the needs of the 21st century.” HB 3 was the spin-off of that timely. Lawmakers rejiggered a number of the system’s outdated solutions, provided pay raises to instructors, repaired a few of the most glaring injustices, and minimized the quantity of money regained by the state from property-wealthy districts. Most crucial, HB 3 represented a much-needed infusion of money for having a hard time schools. The basic allocation was raised from $5,140 to $6,120 per trainee.

But HB 3 likewise worsened variations amongst property-wealthy and property-poor districts. Because of modifications to the method Tier II enrichment financing works, some neighborhoods had the ability to cut tax rates and produce substantial brand-new earnings from their tax base. For others, a minority of districts, HB 3 really produced brand-new issues. Around 10 percent of districts saw a decline in formula financing. This year, Alpine has $220,000 less than it would have had under the old system, even as a few of the wealthiest districts in the state—small West Texas neighborhoods with great deals of oil wealth—saw their financing blow up. Rinehart contrasts Alpine, which has almost no mineral wealth, with Rankin ISD, 130 miles northeast in the Permian Basin oil spot. While Alpine’s financing decreased 2 percent, Rankin’s increased 339 percent. Even though Rankin is predicted to return near to $100 million in regain payments to the state this year, the district is wonderfully rich. “Alpine’s budget is $10 million,” Rinehart explains. “Rankin’s is $14 million. We educate a thousand kids and they educate three hundred kids. So they are a third of our size and have a budget 40 percent larger than ours.”

Rinehart doesn’t resent Rankin’s wealth—she just recently functioned as assistant superintendent there—however utilizes the Alpine–Rankin contrast as a “wild” example of how HB 3 exacerbated injustices, making the abundant richer and the poor poorer.

Hicks, too, has actually discovered. “Rankin just built a whole new school,” he informed me. “They got a new fieldhouse, a new gym. Two new science labs. A turf practice field, a turf game field. A new track, a new stadium. And my buildings were built in 1929.” Rankin is preparing to build 10 brand-new “teacherages”—district-funded housing for instructors, crucial to bring in and maintaining skill in locations with little or budget-friendly houses.

Jeff Davis County, on the other hand, has no oil and gas and really little market; any school financial obligation would hence be borne by house owners through bonds. Hicks’s district has actually never ever provided a bond, in part due to the fact that it would be not likely to pass; the citizens wouldn’t support a tax boost. The school’s ag barn was integrated in 2019 with regional contributions. The band program, suspended for 9 years as a cost-conserving procedure, was just restored in 2023 after a benefactor left his estate to the school.

To make sure, Alpine and Fort Davis are outliers. Most districts saw an instant increase to their financial resources from HB 3, and supporters commemorated a significant financial investment in public education after $5.4 billion in ravaging cuts in 2013. But even for those districts, the sugar rush from HB 3 didn’t last long. According to Chandra Villanueva, the director of policy and advocacy at the progressive not-for-profit Every Texan, the $1,000 boost in the basic allocation was “roughly enough to cover one year of inflation.”

“We were better off after House Bill 3 than we were before House Bill 3,” said Paul Colbert, a previous state lawmaker who has actually invested fifty years dealing with school financing problems. “But to claim that it solved our problems was a giant overstatement of the case. All it did was get us back to where we had been four years earlier.”

Colbert was among the chief designers of the contemporary system of school financing, put together in 1984, when the wonkish Houston Democrat was serving in the Texas House. Today, the 73-year-old works as a lobbyist for El Paso ISD and, more informally, as a walking wiki of school financing history. During this legal session, he has actually been searching some eye-watering truths and figures, the item of his rooting around in TEA information. What Colbert has actually discovered is that state assistance for Texas’s thousand-plus independent school districts has actually been flat for the last years, even prior to changing for inflation. (State help for charter schools has actually taken off, however that’s another story.) In 2014, the state contributed $16.6 billion in upkeep and operations financing; in 2022 it put in $16.9 billion, with the quantity predicted to be up to $14.9 billion in 2023, an especially worrying figure offered growing registration and skyrocketing inflation. When a legislator provided this stat at a legal hearing in February, another lawmaker might be heard discharging a “wow.”

The Legislature, mostly unbeknown to the general public, has actually created a system where it disinvests in public schools while putting an increasing problem on regional taxpayers. Another Colbert truth: The state share of moneying to ISDs has actually fallen from 44 percent in 2011 to 31 percent in 2022. More and more, the tab is gotten by unwitting house owners, occupants, and business owners.

The Legislature has a prepare for this, too. Intent on supplying real estate tax relief, legislators in 2019 plugged in a continuous movement maker, requiring school districts to ratchet down their tax rates as property worths grow. Consider Fort Davis ISD. In 2019, it taxed at the optimum rate permitted under state law—$1.17 per $100 of property worth, or $2,340 a year on a $200,000 home. Today, Fort Davis’s tax rate is $0.97 per $100 of worth, and might drop to $0.87 this year. “Tax compression,” as it’s called, seems like a lovely thing. That is, till you study the small print.

For one, compression doesn’t do anything for public education and might in truth damage it in the long run. Though the state vowed to comprise the lost income—at a cost of $2.5 billion a year—tax compression puts no brand-new money into schools. And from Hicks’s viewpoint, it eliminates his capability to raise money from the regional neighborhood. “They pulled the rug out from underneath me for local collection ability. I don’t have any control,” he said.

This financial legerdemain is mostly unidentified to regional taxpayers, says Villanueva. As an outcome, rather of blaming lawmakers, they look in your area for the perpetrators. “You’re paying more and more in property taxes every year, but your schools aren’t getting any better,” says Villanueva. “Your schools are still threatening to close. They can’t hire enough teachers. They’re in financial distress all the time. So almost by design, it creates distrust for both the school system and property taxes.”

The real estate tax system and the school financing system are inextricably connected, Rube Goldberg–design. Twist a dial here and a light will begin there. Slip an equipment here and spring a leakage there. As state legislators have actually focused on tax cuts over public education financing, the compromises have actually grown clearer. This year represents a prospective juncture. But instead of attempting to resolve the issue utilizing the $33 billion budget plan surplus—a generational gold mine—Abbott and Patrick have actually extremely focused their attention on real estate tax cuts and a school-voucher strategy hated by almost everybody in public education, in part due to the fact that it would threaten to strip a lot more financing from school districts.

The just-completed routine session was a bloodbath. The 88th Legislature started in January with the guv and lieutenant guv assuring to pass a transformative coupon program and a record-setting $17 billion in property-tax cuts. Funding for public education, frequently a banner concern, was rarely talked about. Even the House, the friendlier chamber towards public education, just proposed raising the basic allocation by $140, from $6,160 to $6,300 per trainee—far less than the $1,500 boost required to stay up to date with inflation considering that 2019, according to the Texas American Federation of Teachers. But in the end, instructors and public schools got essentially absolutely nothing.

Teachers and administrators were shocked. Zeph Capo, the president of Texas AFT, called it a “joke.” HD Chambers, the executive director of the Texas School Alliance, implicated Patrick and Abbott of playing a “hostage game” with Texas’s instructors and public school trainees by connecting education financing to coupons. “It’s pretty simple. The governor and Senate says, ‘If you don’t give us the kind of vouchers we want, we’re not giving you any money.’” The House declined to budge, and the routine session concluded without a deal on real estate tax relief, coupons, and other GOP concerns.

Now, the guv has actually guaranteed to assemble several unique sessions to use up the unsettled problems. The initially unique session started 3 hours after the routine one ended, and successfully finished up less than 24 hr later on, with the House turning down the Senate property-tax strategy, passing its own program consisting entirely of property-tax compression, and after that quickly adjourning. Abbott tossed his assistance behind the House strategy. The message to the Senate was clear: take it or leave it. If the Senate yields, the House variation would press some school districts to as low as $0.60 per $100, without any brand-new source of income to backfill for the minimized financing in case of a bad economy.

Abbott has said his objective is to entirely remove the primary school real estate tax. In such a situation, Texas’s thousand-plus school districts would be at the grace of the Legislature for financing—an uncomfortable circumstance, says Villanueva. She believes coupons would then end up being unavoidable. “At that point, it’s like, ‘You know what, we don’t have the money to fund schools. Everyone take five thousand bucks, figure it out for yourselves.’”

That day, if it ever comes, might still be away. But the education system remains in crisis today, and unlike previous difficult times, the state is flush with money. The discomfort, Chambers says, is being purposefully caused by Abbott and Patrick. “Because of this one pet project that the governor has”—coupons—“they are purposely creating a financial environment where every school district in Texas is being set up to fail.”

The result is that Texas schools, already running on “shoestring budgets,” will have a more difficult time bring in and maintaining teachers, said Josh Sanderson, the deputy executive director of the Equity Center, a not-for-profit that represents 6 hundred Texas school districts. They will add deficits. They might need to cut extracurriculars and athletic programs. Some, like Fort Davis, might end up being insolvent and be required to combine with another district, a frequently uncomfortable procedure.

Hicks has actually presumed regarding design his own school-finance system. Idiosyncratic though it might be, it includes aspects that lots of school-finance specialists state are necessary repairs: a more generous basic allocation that instantly increases based upon inflation, more practical formula financing cased on the real-world expenses of education, and counting bond earnings in the state’s decision of whether a district is abundant or poor.

As we were being in his red pickup with the engine idling outside his workplace, Hicks informed me that he’d quit on lobbying the Legislature. He pointed out once again that Patrick and other GOP legislators are attempting to destroy public education by utilizing coupons to privatize schools, and he said that the majority of other political leaders “don’t give a shit about West Texas.” But for the time being he was still combating: composing op-eds, shooting off plaintive missives, asking worried people to call their lawmakers.

Toward completion of our see, I asked Hicks what’s going to occur to his schools. “I don’t know,” he said. “I’m not patient enough to spend time with assholes in Austin, and I’m not rich enough to buy any votes.” TEA has actually recommended combining with another district—more than likely close-by Valentine ISD—however Hicks said this would damage both Fort Davis and the other district.

He appeared resigned to his function as a Cassandra caution of impending doom, predestined to be neglected. He advised me that his grand son goes to school here, which the uncomfortable roadway ahead feels both personal and existential. “If you don’t have a school,” he said, “you don’t have a community.”

Two months later on, Hicks called me with some news. He’d chosen to resign this summer season, signing up with the mass exodus of school leaders that have actually left the occupation in the previous couple of years. To anybody who carefully follows public education in Texas, his thinking was unfortunately familiar: He said he was too exhausted to combat any longer.